Narrative Lock-In

It's time for African venture to tell a new story for a new age

After writing Africa’s S Curves, I felt a bit uneasy.

It was the culmination of 5 years and 50 investments in Africa, starting with my first thoughts around the Frontier Blindspot in 2020. Since that first article, our average check has grown 10x in size, we’ve returned capital to our earliest backers, and closed a bigger magnitude of capital from institutional LPs.

More importantly, I’d like to think we’ve built a reputation for rigor and honesty in the African ecosystem — that we’re able to draw blood from stone in the hardest markets in the world because we’re lucky enough to partner with founders who have a mutual respect for Africa’s frictions.

Still, while I had formed my convictions around the shape of tech adoption on the continent, I had not formed a more pragmatic thesis. As much as I was breaking down Africa’s markets into their present day realities, it did not build conviction in me around what we were actually betting on that others weren’t.

Now, it’s always a taboo to overly-attribute Silicon Valley conviction to African markets, but I also find it important to get your mind out of the local VC bubble as well. Union Square Ventures is one of those legendary firms whose 20-year track record, discipline, and thesis-driven history has always been an inspiration. Here’s how they describe their thesis:

USV invests at the edge of large markets being transformed by technological and societal pressures

African venture has largely focused on opportunities that arise via technological pressures. These waves — fintech, ecommerce, logistics, stablecoin, etc. — have indeed pried open markets and allowed startups to take market share. However, like I’ve extensively covered in Africa’s S Curves, one had to be very careful about infrastructure and timeline when new tech-led models emerged.

It was much harder for African startups to “work downhill” against incumbents when there’s so little infrastructure to piggyback off of. This was compounded by the fact that most of these new business models were transplanted from places where the required digital infrastructure has matured, giving the illusion of a playbook—but one that breaks down in Africa’s offline markets.

Our ecosystem’s myopia around technological pressures came with a naïveté around the social pressures that have been building over the last half decade. We’ve failed to pay attention because our ecosystem is driven by incentives to ignore changes in the social pressures:

The more we highlight tech, the less we must address the misalignment with Africa’s social infrastructure: statecraft, literacy (all forms), trust, etc.

Tech-driven narratives siphon momentum from their developed world counterparts and create a shared vocabulary and playbook.

And perhaps most importantly, we have two tried-and-true social narratives to fall back upon that have worked for the last decade.

If one were to ask almost anyone about the social pressures transforming Africa, you’d arrive at the two pillars of the African venture narrative:

The Population Narrative

Africa will have the largest force of young, digitally-native workers in the coming decade

The Purpose Narrative

Social impact is at the core of Africa’s tech opportunity.

I’m guilty of propagating both stories. I’ve used the first in our pitch decks and my introduction to the continent was through the second. These are the agreeable stories to tell, the kind that gets nods on panels and the kind that can’t get you fired.

But it was exactly this feeling of agreeability that made me so uneasy. It’s no secret that outside of (agent-driven) fintech, the status quo in African tech has not produced consistent, world-beating results. Why should we expect different endings to the same old story?

So let me tell this one a bit differently.

An end to our origin story

Many haven’t accepted it yet, but African tech is at the end of its beginning.

At its peak in 2022, we saw over $6b in venture funding come into the continent. After the bursting of the ZIRP bubble, that number has steadied itself between $2.5 to $3 billion a year, with 2025 likely to land on the higher end of that range.

And we now have results from our earliest vintages. We have 10 unicorns and counting (although the number may actually be closer to 7) and they sit in two buckets.

The first bucket greatly benefitted from Africa’s population narrative, especially during the ZIRP era. Almost all of them claimed their unicorn status during that era when global capital came to seek yield from the “youngest, fastest growing population in the world.” These companies convinced the world’s largest venture funds that Africa’s economy was on the brink of a digital leapfrog. They answered Africa’s infrastructure gap through the brute force of cheap capital.

OPay Series C (2021) — Softbank

Flutterwave Series C (2021)— Avenir & Tiger

Chipper Cash Series C (2021) — FTX

Interswitch Strategic Round (2019) — Visa

Andela Series E (2021) — Softbank

The second bucket greatly benefitted from Africa’s purpose narrative, especially post ZIRP as global equity investors all but left. Almost all have received later stage equity or debt that included development finance institutions (DFIs). These companies convinced foreign aid that building dense, low-cost payment rails for the offline majority was itself a development outcome. They answered Africa’s infrastructure gap through the global mandate for financial inclusion.

Wave Debt Rounds (2022 & 2025) — IFC, Norfund, Finnfund, BII

MNT-Halan Series B (2024) — IFC

Moniepoint Series B (2021), Series C (2024) — IFC, BII, FMO, Proparco, Swedfund

Tyme Series B (2021), Series C (2022) —BII

Looking back, the population and purpose narratives have been wildly successful. The promise of a demographic boom supercharged Africa’s venture funding with billions of dollars when capital was flowing. When it stopped flowing as readily, the continued promise of the “double bottom-line” helped to justify the need for impact-driven capital to step in.

But here’s the thing. The population and purpose narratives are dead.

The signs of narrative lock-in

When a venture market’s social pressures change, it takes time for its narrative to catch up.

In the U.S. for example, capital continued to chase crypto NFTs well after their 2022 crash, pivoting into collateralized lending and licensing. A similar pattern played out with the metaverse. The vast majority of these lagged bets fail as story, capital, and reality finally adjust.

In Africa, we are in a period of narrative lock-in. Over the past few years, the social pressures in Africa’s tech ecosystem have fundamentally shifted, but our ecosystem’s narrative has been stubbornly stagnant. This has been especially damaging because—as mentioned above—African venture does not have a menu of LP-approved stories to draw from. Unlike in Silicon Valley, we cannot quickly pivot into coding co-pilots, in-home robotics, or nuclear fission.

Instead, we are trying to force capital into the old narrative.

Narrative lock-in shows up in the data through a few clear features:

Investors who have a mandate to invest in the outdated story gain a larger share of total funding as others wait to reorient around something new

A rising share of debt and grant capital crowds out equity as appetite for high-risk ownership fades

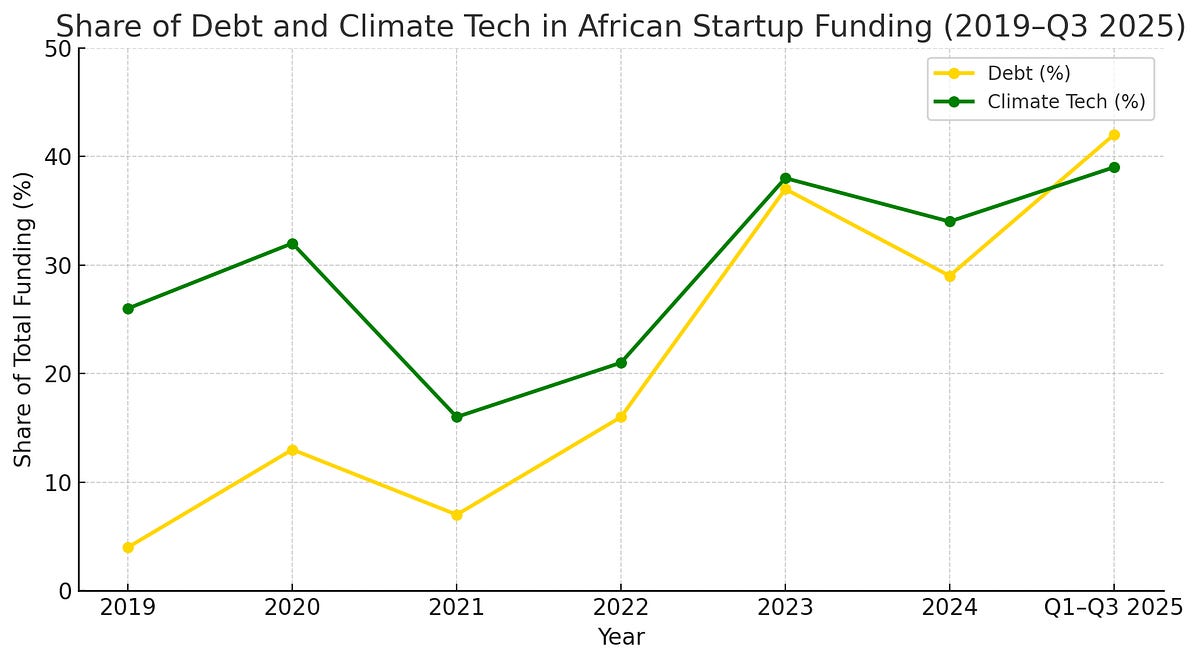

You know, something like this:

Debt now represents 42% of Africa’s startup funding in 2025 — an all-time high. By comparison, both Latin America and Southeast Asia saw around 5% of their venture funding raised as debt in 2024.

Climate now accounts for about 39% of Africa’s startup funding 2025— an all-time high. Southeast Asia saw climate make up about 5%1 of their venture funding and Latin America saw about 8%.2

If we dive a bit deeper into the data, you’ll see that both these trends converge in energy sector funding, particularly last-mile solar. It’s the last refuge where climate-mandated capital can write substantial checks, especially through later-stage debt. Roughly 75% of energy venture funding now comes in the form of debt, largely flowing to last-mile solar—a model that has absorbed significant capital but struggles to generate venture-scale returns.

In the meantime, equity deals in Africa have fallen off and stagnate at $1.5 to $2b a year. Pre-seed deals have especially struggled and remain around 1.5% of total venture funding compared to about 5% in the United States. Worse, dependence on grant funding more than doubled in African pre-seed since 2021. To give you a sense of how weak pre-seed has gotten: half of Kenya’s 2025 pre-seed funding has been grant-based.

This creates a stark disconnect between a story of ecosystem recovery (+40% year-on-year!) and the actual composition of lower-risk capital that’s fueling it. In 2025, equity grew by 25% while debt grew by almost 80%.

In light of the above, it's no surprise that anxiety around returns is at an all-time high. But our reaction has been to argue for more concessionary terms. I hear calls to further bend capital to compensate for soft returns—evergreen funds, subsidized hurdle rates, tokenized exits to retail. Older African funds have already been extended to 15 years on average. Each of these proposals shares a common thread: they treat the symptom, not the cause.

On the other hand, others have mistaken narrative lock-in for a verdict on venture capital in Africa itself. They have chosen to write the model off entirely.

I disagree.

Rather than give in to this deceleration, we need to first clarify when the old narrative stopped being true and align African venture with the forces now reshaping global power. We can either compete on those terms, or remain trapped in a narrative that explains the past but cannot finance the future.

The (African) Alignment Problem

Population

Africa will have the largest force of young, digitally-native workers in the coming decade

African venture’s population narrative — at least as it was once told — ended on November 30, 2022 with the release of ChatGPT 3.5. Africa’s social pressure around population had deeply changed.

In the coming decade, Africa needs roughly 150 million jobs, or 15 million a year. Today, it creates closer to 3 million formal jobs a year. That gap implies that 120 million youth will be unable to find formal work by 2035, equivalent to the population of the world’s twelfth largest country.

Our ecosystem has struggled with the jobs question and has predictably found a nail for its narrative hammer. We have reports that outline 100 million ‘green’ jobs in Africa by 2050 while later predicting 3.3 million such jobs by 2030. Another predicts 75 million green jobs in 25 years and yet another, 600k solar jobs by 2050.

All but one of the reports predicting African job growth I found in the last 5 years were focused on green jobs. That lone report from 2022 predicted 44 million jobs given Africa’s internet penetration reach 75% of the population, something that could take another 20 years. Narrative lock-in.

Ironically, energy will play a central role in Africa’s population challenge. However, I believe it’ll have less to do with last-mile solar installs and more to do with the incremental cost of compute.

To put it plainly, the world’s youngest, fastest-growing, most digitally-native population is set to compete for jobs-to-be-done against a flood of agentic machine labor over the next decade.

It’s a fight that Africa’s youth will not win head-on. If we stay the course, we will risk the largest unemployment crisis in history while simultaneously squandering one of the largest opportunities of this century.

Therefore, even though artificial intelligence will apply technological pressure on the continent —in the way it does everywhere not named America or China — the social pressure it will exert on Africa will be uniquely severe.

And where our reliance on the continent’s demographic destiny ends lies a moment to realign Africa’s economic contract with the world. But to do that, we must first confront the second pillar of our narrative.

Purpose

Social impact is at the core of Africa’s tech opportunity.

If Africa’s population narrative was ended by technology, its purpose narrative — at least as it was once told — was ended by policy. More precisely, it ended on July 1, 2025, when USAID closed its doors.

This realignment has caused widespread suffering and will harm millions more. There is room—and need—for both impact-oriented and commercially-driven capital in Africa. However, I worry that our dependence on the double-bottom line has left us exposed.

It’s not just the American administration that’s been shifting.

For the first time in three decades, the United States, the United Kingdom, Germany, and France have all cut official development assistance (ODA). If they cut ODA again in 2025 — which looks likely — it will be the first time ever all four countries have decreased ODA two years in a row. Sub-Saharan Africa will be hit hardest, with a projected decline of up to 28% or about $10 billion.

Roughly 42 percent of Africa’s private capital flows through development finance institutions (DFIs), often via concessionary ODA pools designed to absorb risk on behalf of commercial investors. There are billions of dollars ringfenced for this and African VC has greatly benefited from the catalytic effect of these anchor investments.

However, slowing ODA is just a leading indicator. All over the Western world, the mandate for all state-led foreign aid is weakening.

This year, the UK confirmed it will cut aid by £6.1 billion in order to raise its defense spending to 2.6% of GNI. Their Minister of International Development resigned stating that “undoubtedly, the postwar global order has come crashing down.” The UK plans to increase defense spending to 3% of GNI.

When Sweden cut aid recently to divert money to Ukraine, their officials put it plainly: “There isn’t a secret printing press for banknotes for aid purposes and the money has to come from somewhere.” Elsewhere, Germany cut the budget of its foreign aid office by almost $1 billion. In France, a €1.3 billion cut to foreign aid in their draft budget ended up being increased twice to cuts of over €2.3 billion by the final budget. At the same time, Berlin has doubled its defense spending and Paris has increased its own by 40%.

We are also starting to see this support for these priority shifts by voters. In the UK, only 20% of those polled opposed the tradeoff of cutting aid for defense. Ultimately, survival has priority over sympathy — as it naturally should.

Now imagine what happens as the social mandate for impact investing in Africa ends. The signals are starting to appear. The result would be a hollowing out of African venture’s primary capital base, a collapse of strategies built on concessionary risk, and a forced realignment of the ecosystem.

Impatient capital

Africa’s previous story was tailored for the previous twenty years when the world enjoyed overflowing cheap and conscious capital. That’s over. If the internet era rewarded Africa’s potential, the AI era will demand its agency.

The underlying virtue of Africa’s population and purpose narratives was patience—a sense that Africa’s venture returns are tied to destiny rather than demand. I believe that our ecosystem’s belief in patient capital created a culture of passivity. Our funds wait for that YC invite, that Silicon Valley lead, that low valuation multiple. If patience is the virtue, then waiting is the strategy.

But look around us. The world is changing at a frenetic pace. Synthetic intelligence is tradable. Tokenized dollars are flowing. The physical world is uploading. As our ecosystem struggles with narrative lock-in, a new story is being written globally—with or without us.

It’s pretty clear to me that the unease I feel comes from a sense of impatience. I wrote in Africa’s S Curves that I do not believe in leapfrogs in Africa. I believe in steeper slopes—that tech accelerates what’s possible with existing channels that have cracked distribution in Africa’s high-friction, semi-formal markets.

The AI era amplifies this. Its technologies don’t just create steeper slopes, they create step-changes. If you’ll allow a relativity metaphor: our current disposition is to stretch time—waiting for markets to mature, for infrastructure to catch up—but AI compresses distance, lowering the threshold to scale: coordination, expertise, formality, headcount, cost. At its best, AI will shift Africa’s bottlenecks from dependencies to demand—and potentially do something no other technology has ever done for the continent: create global leverage.

This also means that more often than not, the continent’s biggest opportunities will come in impossible-looking forms made possible by this step-change. This will be an era that amplifies founder agency while punishing low-conviction disguised as patience.

To that end, here are the convictions that underpin my impatience:

Africa’s core inputs—money, labor, and land—are becoming more programmable and tradable than ever before.

Artificial intelligence in Africa will be diffusive rather than discrete—the substrate that finally enables the continent’s human-machine infrastructure to coordinate at scale.

Together, these shift the African venture opportunity away from domestic consumption, impact metrics, and leapfrog potential—toward productive capacity, critical assets, and global leverage.

Next time, the thesis and the companies we’ve backed. Stay tuned!

This report cites 16% of total value for climate tech in Southeast Asia (H1 2025). I believe they have a made a mistake. $131m of climate tech deals / $2.55b of total deal value = 5%.

Full year African venture funding numbers have been released. Debt ended 2025 at 37% of total funding and climate tech at 38% of total funding according to Africa: The Big Deal.

Incredible analysis on narrative lock-in. The stat that debt now represents 42% of African startup funding vs only 5% in Southeast Asia really hits home - it basicaly shows how investors are masking risk aversion as patient capital. I've seen similar patterns in other emerging markets where the shift to debt heavy financing usually precedes either a reset or total stagnation. Your point about "impatient capital" being the antidote is spot on, tbh Africa needs founders who move fast enough to create global leverage before the ecosystem adjusts.

I think we run the risk of throwing the baby out with the bathwater. Africa needs more risk capital and still needs the patient capital that has been provided historically (impact, DFI). We do need to test the narratives surrounding the venture class and what that looks like given where global dynamics are heading. I think as the world is moving towards a multi polar world, the themes and focus will also find a home on the continent. Opportunities in industrialisation, robotics, resilience, localisation, adaptation will be areas where the venture capital industry can lead in. Maybe that looks more like the beginning of silicon Valley where there was significant investment in hardware and physical infrastructure than the software driven age we have found ourselves in.